The experience-led enterprise

Summary

Formalized UX design at IBM. Developed common language, principles and practices, enabling integration UX quality into IBM’s corporate performance management system. Led a cross-functional squad to envision, design, deliver and maintain journey management products, leading to a 50% average improvement in complexity scores among adopters in IBM & public sector clients.

Architected and operated the IBM Journey System, a management system to drastically simplify IBM’s value proposition to developers and improve key developer journeys. Collaborated with IBM growth team to develop shared platform services that drove an average of 80% SaaS offering revenue growth, and 300% improvement in product consumption to adopting products in a 12-month period.

Led a research pilot on IBM’s application modernization journey, resulting in a per-product average of 4x increase of digital leads, 2x increase in trial conversion, and $1-2.4M additional digital revenue within just 1 quarter.

Part 1: Umwelt

We shape our tools, then our tools shape us.

The common pigeon is endowed with microscopic magnetite particles in their inner ears, allowing them to sense Earth's magnetic field and "feel" cardinal directions. Yet for all their directional prowess, pigeons have a terrible sense of taste– 50 taste buds to a human's 10,000.

Meanwhile, dogs live through their noses. Their acute sense of smell is 10,000x more powerful than a human’s, and makes it possible for them to do things like sniff out explosives, track lost hikers, or detect cancer in the human body. Yet as anyone who has ever walked a dog is aware, dogs understand neither right angles nor straight lines – they do not possess basic concepts of geometry.

Each living, conscious being embodies a unique perspective of reality – something 18th century naturalist and philosopher Jakob von Uexküll referred to as an Umwelt.

This perspective is not interchangeable across species, because the origin of this Umwelt is encoded in our physiology: a physical infrastructure of sensors and processors that make living things sensitive to some events in the world, and completely ignorant of others. Confined to our own bodies, we will never understand what it is truly like to be a a pigeon flying south for the winter or a beanstalk basking in the Texas sun, let alone a mushroom or a tree.

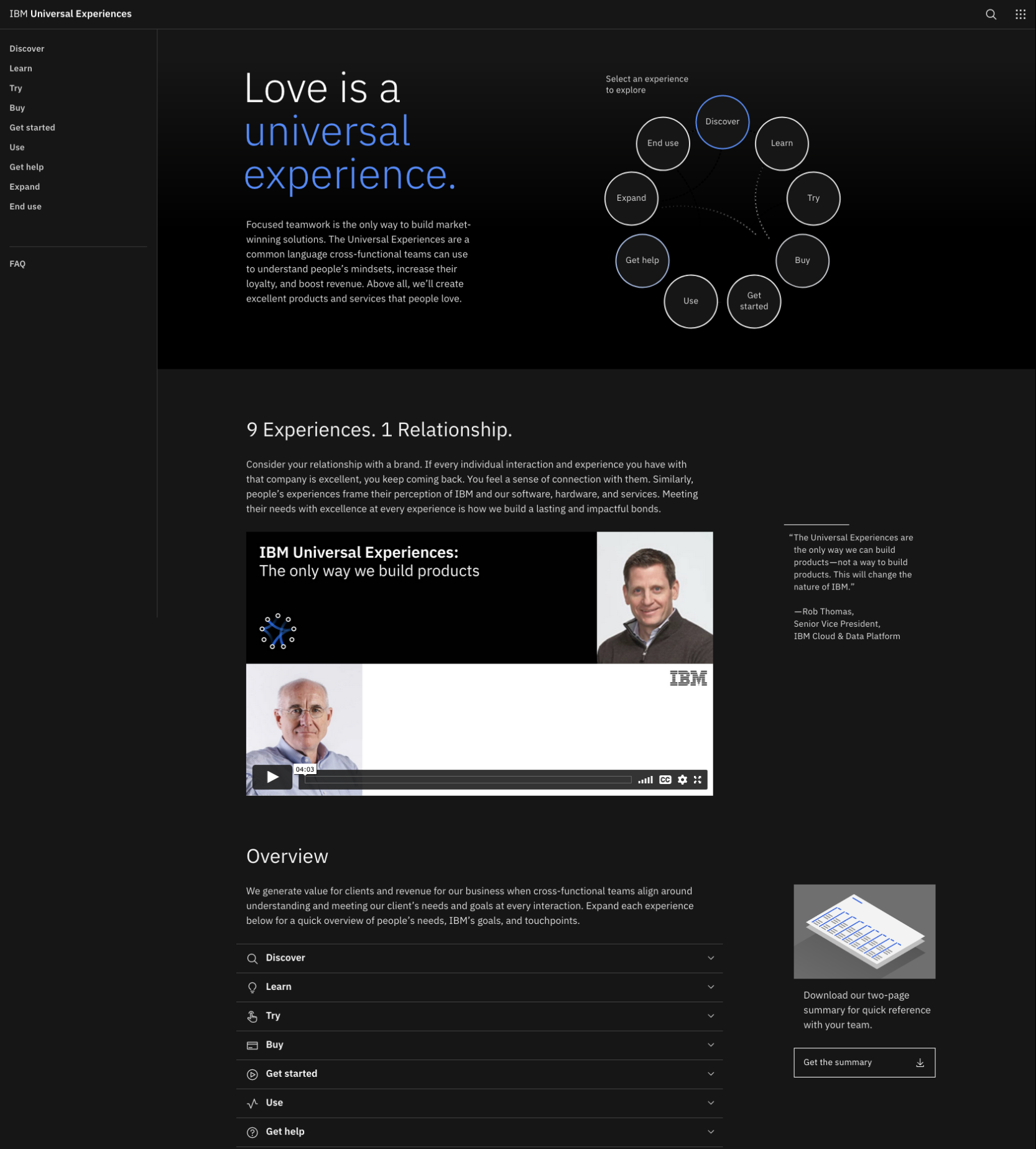

In 2017, I was asked to define IBM’s user experience design practice, I convened experience experts to author the Essential Experiences: a shared language for teams to design and deliver end-to-end product experiences. I used this framework as the basis for new enablement experiences I delivered and scaled to cross-functional teams across IBM.

Having conducted research about business leaders and their prioritization practices, I architected, designed and drove adoption of new journey infrastructure to help IBM sense, respond, manage and govern user experience performance with the same rigor as our financial performance. Serving as both program manager and design lead, I staffed a lean team of designers, researchers and engineers to bring a first iteration of Project Radar to life.

In eight months, we delivered and supported a self-service experience for researchers, offering managers, designers and marketers to define user needs, capture experience quality, manage toward improved experiences, and connect with other teams about known dependencies.

It turns out that enterprises have an Umwelt, too. As individuals, we adopt the Umwelt of organizations each time we step into the office, or open up our computers and log into our email accounts. While we inhabit these social constructs, we become sensitized – and desensitized – to an entirely different set events in the world.

And as with creatures, the Umwelt of our enterprises is encoded in our infrastructure. Instead of rods, cones, and cortical processors, we build analytics tools into our products, create data objects in our management systems, establish object relationships or business processes to tie employee compensation to some presumably important data point.

This begs the question: what business objects can you find in your management system? What concepts can your organization “see?” And how does that change the way the enterprise behaves?

I often meet designers at large enterprises who still report going through contortions to “communicate in a language the business understands” — as if “the business” is some “other” domain, to which we do not yet belong.

But the truth is, for those of us trained to see the world through the lens of the human experience, our enterprises are not yet a place where we belong. And though they may be professed in Keynotes and design thinking enablement sessions, the concepts we use to deliver great user experiences—people, needs, experiences—have yet to make their way into the information systems of the modern enterprise, where part numbers, utilization rates and revenue forecasts still rule the day.

But as designers, we aren't helpless, either. Unlike the pigeon and the dog, the enterprise is not confined to the body. It is a designed system; as stewards of the enterprise, we can give ourselves new senses, change the way we process information, and by doing so, manipulate our own behaviors and habits.

As John Culkin of Fordham University famously said, "We shape our tools, then our tools shape us.”

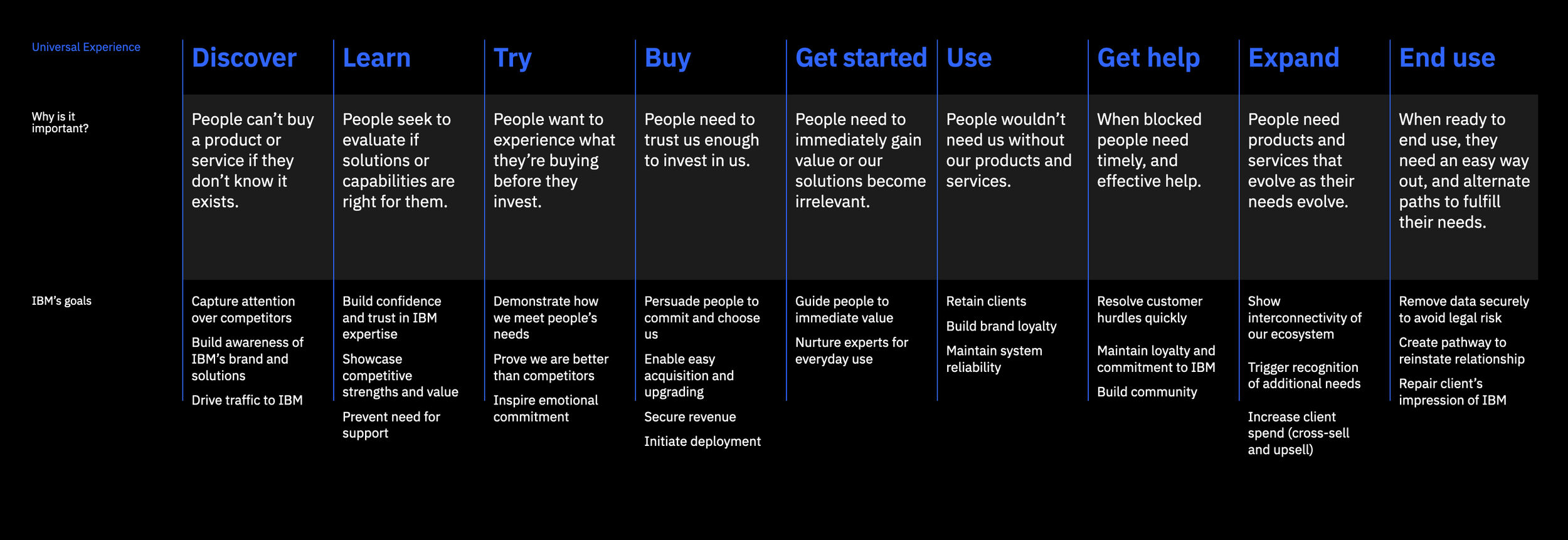

The Essential Experiences

From exploring our product pages, to attending an event, to installing and configuring a products, to talking with customer support—people are interacting with this organizational all the time. Every experience we deliver is an opportunity to improve our relationship with the customer.

Yet too often, we fail or forget to consider each of these experiences. And even just one bad experience is enough to sour the relationship. How do you align a myriad group of discipline and organizational silos on a common view of the customer experience?

End-to-end

Convening product design and customer experience experts, I defined a canonical set of experiences that represent customer and user needs across their relationship with us. Importantly, this framework reminds teams that these are contexts ours users experience, whether we’ve intentionally designed for them or not – and I chose to depict the Experiences in a circle to symbolize completeness – compelling product teams to at minimum consider how their product addressed all 9.

Many product designers spend most of their time with Use. Of course the experience of using our products is important because it’s how people get their job done, using from our products. At IBM, Id argue that we spend too much time thinking about “Use” and not enough on everything else.

Discover is important because people can’t buy a product or service if they don’t know it exists.

Try is important because people want to experience what they’re buying before they are willing to invest. They want to get their hands on the thing that they will be purchasing and test it out to ensure it fits their needs.

Get started is important because if a person can’t immediately complete tasks or gain value, they’ll never experience the aha! moment that convinces them of our products worth.

When people get timely and effective Help, they keep getting value from our products and services rather than getting stuck.

And just as each of these experiences is characterized by a customer need. they also represent corresponding business opportunity for us: great discovery drives product and brand awareness, great trials drive conversions, great help experiences support customer loyalty and retention.

/design/experience

I authored, designed and coded the Essential Experiences digital property as a single channel for content about the framework, including Camp W (our in-person educational experience) and Radar (our software system for managing against experience). Each of the 9 experiences included fine-grained clarity into users' & IBM's goals competitive benchmarks, case studies, and metrics.

In 2020, the Essential Experiences were updated and repackaged as the Universal Experiences. Of the Universal Experiences, SVP Rob Thomas hailed it as “…the best IP ever written on design.” The Universal Experiences remains IBM's official experience framework today, and are an essential foundation for IBM’s adoption of product-led growth tactics.

Project Radar

Project Radar began life as a provocative slide that asked, “What if we could make decisions about user experiences the way we make other product decisions, by managing our experiences against the competition?” and explored it with a concept sketch.

One senior vice president who set his eyes upon our slide, and was so perturbed and convinced by the sketch and the data displayed therein that they ordered the rest of his portfolio be evaluated in a similar manner. This unnamed senior vice presented had evidently missed our disclaimer that the data in this visualization was, in fact, fake.

This insight – that IBM’s leaders might learn to care about and invest in excellent experience if given the tools to see – began a multi-year project to establish the practices and tools necessary to operationalize user experience design at IBM.

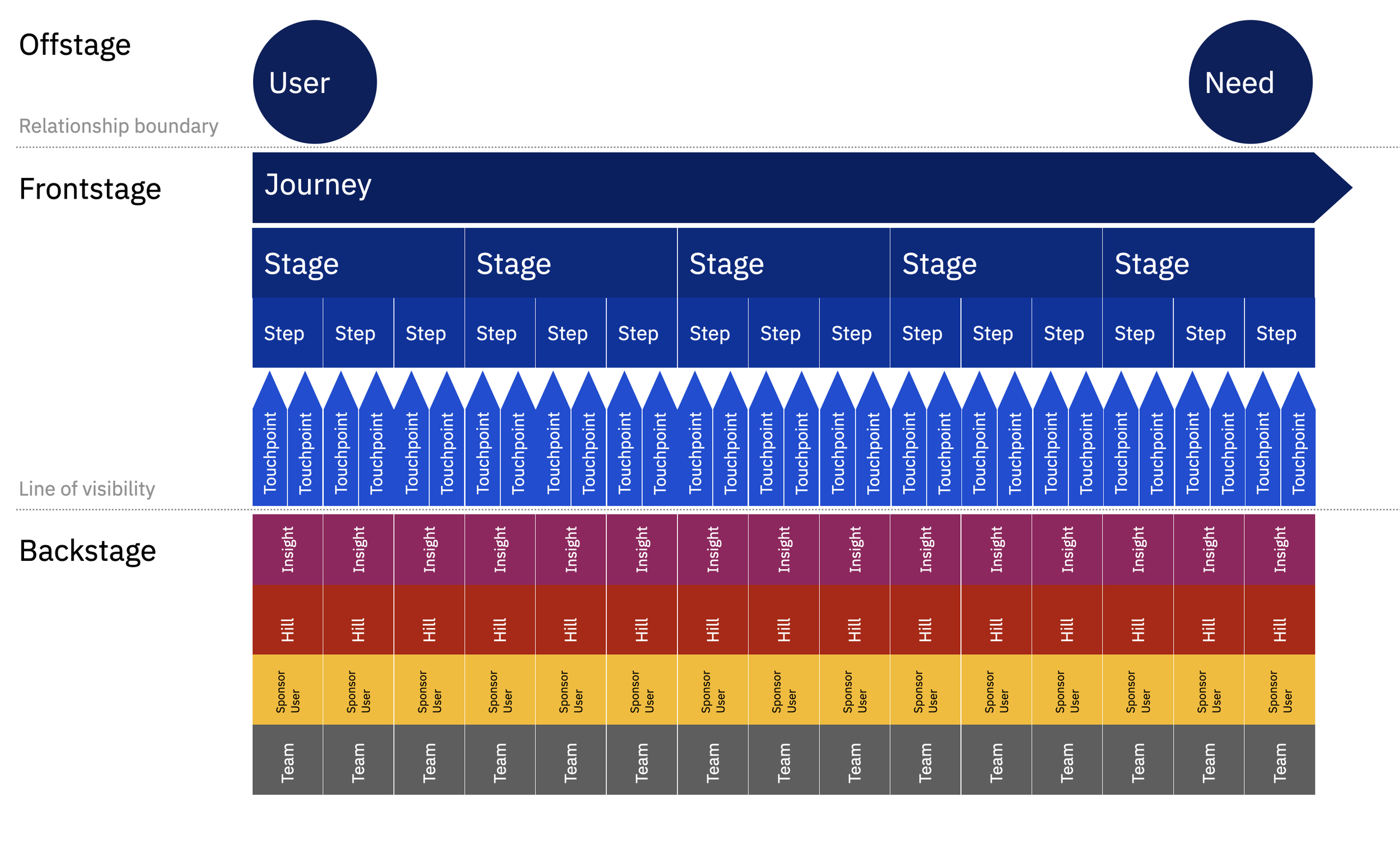

A journey management system

While journey mapping tools and campaign automation products existed, Radar was the first journey mapping platform in the industry that delivered comprehensive journey management capability across a complex portfolio of products, services, and touchpoints. This quality was attractive not only to IBM, but to clients such as ADSSSA and Cisco, who in briefings often asked for ways to use Radar in their organizations.

Radar was also the first functional software product written in React leveraging the new IBM Design Language (aka “Duo”), and became a test bed for new components and interaction patterns.

In 2018, I was awarded an Outstanding Technical Achievement Award for my work to design and lead the development of IBM Radar.

A human-centered model

Early in the project, my team and I conducted a backstage audit of over 130 tools that our cross-functional peers used in order to better understand the Umwelt they inhabited. We saw HR system that spoke of roles, levels, employees, managers. Enterprise Performance Management systems that represent and display revenues, expenditures per offering and division. Project management backlogs that catalog issues, sprints, roadmaps.

And we observed differences in the way different people using these tools saw the world. We saw Product Manager’s world revolve around the product, or in data terms, a PID, which had associated clients, revenue, and so on. Digital Marketers’ performance measured by the number of qualified leads they can generate off of the web pages they own. And in all of this, we started asking ourselves…what about the people we serve? Users? Where are needs? Where are experiences? Until these things are part of the information systems of the world, we observed that user experience leaders were lost, speaking a foreign language.

Object modeling has been an important aspect of my design practice. These models are more than just database schemas. All practices, domains, and disciplines are founded upon a conceptual model: a representation of a system, made of the composition of concepts that help people know, understand, or simulate the subject the model represents.

Articulating this conceptual model, such that these concepts become shared language amongst teams and organizations, is what enables organizations to work together, "see eye to eye," and sharing lenses and perspectives based on a common ground truth. To align on an object model is to confirm that we share an ontological basis for reality. I often find they are a prerequisite for effective collaboration, and the basis to collectively envision new futures.

This is an early draft I developed of an object model for the human-centered management system: “Users” come to IBM to fulfill a variety of “Needs.” They go on “Journeys” to fulfill them. To complete the Journey, they need to fulfill certain tasks and steps, which require interaction with various Touchpoints, whether they be “Offerings,” “Content,” or “Shared Services.”

Camp W

To drive adoption of the framework, I struck a collaboration with Eleanor Bartosh to design and pilot a new educational experience ("Camp W”). This two-day, hands-on bootcamps intended to help teams elevate core design research skills, and translate market and user insights into competitive experience advantages.

Top right: Camp W, Toronto

Bottom left: Camp W, Shanghai

Bottom center: competitive experience assessment activity

Needs over Offerings

As Ted Levitt famously stated, “People don’t want quarter-inch drills. They want quarter-inch holes.” Although Radar prioritizes Needs over Offerings, starred needs enabled product teams and leaders to always have a view of the Needs that mattered most to them.

Map multiple paths

There are many ways to fulfill the same need. With Radar, researchers might map multiple journeys, enabling comparison against other supported routes – and even competitors’ journeys.

Managing backlogs across silos

For a complex use case, a user journey might require them to interact with dozens of offerings and touchpoints to fulfill their need. Product managers often struggled to coordinate and orchestrate their peers to deliver a coherent journey to users.

Radar enabled product managers, designers and researchers across offerings and touchpoints to work together against a common journey. After integrating an Aha! account to their product listing in Radar, researchers can leverage insight from Radar to directly impact an offering’s backlogs, creating ideas and issues associated to a journey.

Find gaps and seams

With an integration with Amplitude, teams could corroborate their investment and design decisions with real and actual user behavior data (ex. task completion).

Although traditionally an extremely time-consuming analysis, I worked Rick Sobeisiak (IBM Security) and Iris Riviera (System Z) to develop a simplified scoring model for complexity analysis that, incredibly, still achieved a high degree of correlation. Within months of release, teams adopting the complexity analysis framework and actioning their findings with Radar began reporting up to 50% reductions in complexity.

Case study: IBM Cloud Platform

In 2017, IBM Cloud set off on a massive effort to unify myriad platform experiences from both the first party IBM Cloud Platform and Softlayer. In order ensure that the unified platform supported real and actual customer needs, platform squads were directed to map common flows across the platform and identify opportunities to close gaps.

I quickly struck a partnership with Christopher Garrison (Design Lead), Adam Waugh (Designer) and Avery Rowe (Offering Manager), who became critical sponsor users in the development of Radar. Drawing from our experience in applying the Jobs to be Done approach in Camp W, I worked with them to identify ways to support the then-arduous customer journey mapping practice. Then, we designed a process to translate issues identified in Radar to actual improvements in the product.

Radar ultimately reduced the time it took for teams to map and analyze a journey from 3 days to just 3 hours. Of the issues identified by Radar, over 50% were delivered and closed within a quarter. IBM Cloud Platform became a key partner and benefactor of a journey-based approach to platform experience design.

Top: The as-is experience of managing a journey on the IBM Cloud Platform, circa 2016

Bottom: Christopher Garrison and Adam Waugh deliver a status update in Cloud monthly operating review on issue burndown from Radar

Part 2: Highways

Interstates

In 1919, a young Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower joined a US Army Motor Transport Corps convoy on “History’s Worst Cross- Country Road Trip” along the Lincoln Highway from Washington, DC to San Francisco, CA.

The trip took 62 days to reach the West Coast. Of 81 vehicles that set off, nine were scuttled, lost to terrible road conditions and mechanical failures. Of nearly 300 men who set off in Washington, 21 were too wounded to complete the journey.

America had been paving its city streets since the 1800s. The transcontinental railroad had been completed in 1869. So why was Eisenhower's journey so treacherous?

The culprit was clear. Eisenhower's route crossed through 11 states. In the absence of a federal highway administration, the road network was governed by state a local city councils who regularly prioritized local and regional needs at the expense of effective interstate travel.

Eisenhower’s memory of the ill-fated convoy, coupled with his experience with the German “Reichsautobahn” during World War II, helped him pass the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. The Interstate system prioritized key routes of travel across state lines and invested billions of dollars to build new highways or bring existing roads to a strict standard of excellence: 12 ft travel lanes, 4 ft shoulders, and a common design system for wayfinding and signage along Interstate routes.

To date, the Interstate Highway System is the largest public infrastructure in American history. Its impact on interstate commerce, the democratization of cross-country travel, and the unique auto-centricity embedded into American culture cannot be understated.

In 2017, a team of design researchers observed users beginning an unbranded search from Google, and obtaining at a trial of Watson Assistant, IBM’s AI-powered chatbot authoring product. During the task, users wandered from webpage to webpage, each claiming to offer the next best action, but each contributing to a growing mountain of frustration as users failed to orient themselves within the IBM digital ecosystem. At the time, IBM had hired over 1,500 formally trained designers, and had badged over 150,000 practitioners in Enterprise Design Thinking. So why was this customer's journey so treacherous?

Until 2017, IBM shared many characteristics with the US highway system of 1919: a patchwork of myriad products and services governed individual business units and discipline-oriented teams, at the expense of effective end-to-end solution design. Indeed, if you traced the paths users took through our digital properties, you would likely encounter web properties governed by a dozen different teams, each with duplicative design objectives and often conflicting metrics for success.

Consumption data from Digital Business Group told a richer story: virtually none of our customers ever came to IBM for a single offering. They came to fulfill a need that required them to enlist the capabilities of multiple offerings. A user consuming Watson Assistant might look for a place to store chat records in a Cloudant database, ingest a corpus and train a NLP machine learning model in Watson Discovery, then integrate their chatbot with customer-facing applications with API Connect.

This was a problem fit for a federal highway administration. In 2018, I struck a collaboration with the Digital Business Group's Customer Experience & Growth team under Harriet Fryman to architect a program that could bring this journey-driven management approach to the developer experience across all of IBM. Called the Journey System, our program reshaped the way IBM showed up to our developer users, changed the way IBM's business leaders set strategic priorities and laid the management groundwork needed to sustain a modern experience-led enterprise. Though changes in IBM strategy shifted the focus of away from developers in 2019, the core tenets of the program are applied at the IBM level in IBM's Marketing Conversations.

Building on the key journeys established by the Journey System, I led a research effort to understand the end-to-end application modernization client experience. The synthesis of my research aligned IBM teams on a shared understanding of how to improve one of IBM's most strategic customer journeys: our clients’ path to the hybrid cloud.

"Any organization that designs a system will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure."

Melvin Conway

The Journey System

As IBM Design’s attache to IBM’s digital sales organization, I worked with Harriet Fryman, Sarah Brooks, and Melissa Dain to design a program architecture for the Journey System program. Over the course of 6 months, we aligned leaders from the Design Program Office, Digital Business Group, and key business unit leaders in Cloud & Cognitive to deliver the Journey System. In 2018, Sarah and I presented the program to Ginni Rometty and the IBM Board of Directors, winning their advocacy and support.

Our external evangelization of the program also inspired imitation movements across the business. For example: the IBM Employee Experience Team kicked off the "IBMer Journey System" sponsored by Diane Gherson. This enabled over 25 HR professionals on mapping end-to-end journeys, supported by Radar. The team successfully managed, measured, and designed improvements to five core employee needs and ~25 employee, manager, and executive journeys.

Taking inventory

Because IBM’s digital go-to-market experience revolved around offerings, customers often struggled to discover the right IBM offerings to fulfill their needs. But what were those needs? And on which of the near-infinite set of needs would IBM base its digital presence?

In collaboration with Harriet Fryman, I designed a method and process for identifying new key journeys, evaluating criteria such as customer importance, size of market opportunity, offering affinities and expansion opportunities, and internal stakeholder maturity. I coached Harriet's team of design researchers and business analysts on the process of identifying and validating the first series of 12 Key Journeys for IBM. Teams were expected to build dossiers and “pitch” them to the Journey System team and its executive sponsors for prioritization.

Adopted by Bob Lord's Digital Business Group, these journey helped focused IBM's marketing and sales investments on a smaller set of priorities.

Below: a sample of artifacts from a dossier I authored for “Build an AI-powered Customer Support Experience.” A complete dossier required a high-level market summary, a customer-side target “reference” architecture, expansion opportunities, and last but not least, a documented journey in Radar.

Cross-offering funnel management

At the time, IBM currently managed at the offering level, yet few needs were fulfilled by only one offering. To be truly client centric, we need to develop a view of the business based on what a client wants to do with IBM.

Our team developed the Journey Key data model to track a user’s relationship with IBM as a brand along an end-to-end journey, rather than with discrete offerings. Cross-offering, cross-touchpoint journey-based tracking enabled us to optimize conversion from trial to purchase, identify product adoption and cross-sell opportunites, and improve customer retention.

This is an example of an affinity diagram describing usage relationships between offerings at IBM, centered on Watson Assistant (neé Conversations). These diagrams indicated the paths users took to incrementally fulfill key journeys. A chatbot developer may start with simple but gets production-ready chatbot using Watson Assistant with Web Apps and DevOps offerings; as the solution scope increases, developers adds a Cloudant database for storing transcripts; finally, they add Discovery to the solution to address the long-tail of questions.

This type of analysis was also an important tool to resolving conflicts between offering marketing teams in competition for marketing dollars. For example, Usage of Watson Assistant commonly indicated usage of other products such as Discovery and Availability Monitoring. In fact, investing in marketing for Watson Assistant was a stronger driver of Cloud Object Storage adoption than investing in marketing for Cloud Object Storage!

Lastly: the Journey Key served as a valuable aid to our sellers who used leads passed from the Journey Key to initiate very time-sensitive yet informed conversations about customers’ needs. For example: in 2019, the Modernize a legacy application journey key identified ~200 new digital leads generated per month; delivering anywhere between $1-$2.4 in additional signings per quarter.

Shared services for nurture experiences

To identify opportunities to raise the experience of all our key journeys, I facilitated a series of workshops that aligned digital marketing and sales teams to identify and prioritize 3 new "shared services" components to improve all Journeys. Using the Build an AI-powered customer support channel Journey as an exemplar, I led a subset of the Journey System team to deliver a prototype of a to-be experience leveraging these services. In this capacity, I refined the concept for these shared services into a series of wireframes and provided creative direction to the team.

Sarah Brooks and I shared this prototype with Ginni Rometty and the IBM Board of Directors, engaging them in compelling conversation about how to bring the brand experience embodied by "the IBMer" into a digital channel. The prototype led to the standardization of what is now known as "solution pages," and catalyzed for IBM's investment in WalkMe.

Since adopting these patterns, IBM has recorded a 6X increase in product adoption, 4X higher conversion rate, 80% revenue growth of digital offerings, and 300% improvement in product usage, consumption, and user retention.

Right: Enhanced "starter kits" and landing pages focused on needs, not offerings. These became known as "solution pages."

Bottom: Embedded guidance (dynamic content model and contextual access). This prototype was the catalyst for IBM's investment in WalkMe.

Not pictured: Surfacing interactive tutorials on the solution page. 75% of buyers make a decision within 15 days of experiencing the product (e.g., demo or actual product). Unfortunately we could not find a technically feasible way to deliver this.

In addition to contextual inquiries with Garage teams as they delivered hybrid cloud adoption experiences to clients, I led fine-grained interaction research with developers, architects, and other subject matter experts, as well as executive interviews with client CTOs and CIOs at Hertz and MITRE.

From contextual inquiry at Hertz: IBM Cloud Architect Reedy Feggins briefs a team of developers from Hertz on the continuous delivery pipeline that will be used to incrementally deliver the microservices that comprise Hertz's modernized rates engine.

The Journey to the Cloud

As part of the Journey System program, IBM's Hybrid Cloud leadership requested our support to facilitate and orchestrate one key journey amongst our inventory: Modernize a legacy application.

Sponsored by the IBM Cloud Private team and leveraging relationships in the Garage and sales organizations, I led a research effort to observe, synthesize, and identify opportunities to improve the end-to-end application modernization client experience, both frontstage within our clients’ domain, and backstage within IBM.

Strategic as the journey was, we quickly learned that the teams delivering the offerings and digital experiences along the journey didn't have a common understanding of the experience, nor did they have a common understanding of the events and decisions in our clients' world that led up to an application modernization project. The absence of this common understanding meant that IBM failed provide a coherent a digital experience for the journey at all.

In fact, own IBM Garage teams were reluctant to recommend IBM modernization-related products to clients. Our offerings scored forgettably low in modernization-related searches. If a modernization client found their way into the IBM digital ecosystem, we offered little guidance on how to select the right offerings.

The synthesis of my research aligned IBM teams on a shared understanding of how to improve one of IBM's most strategic customer journeys. We uncovered surprising insights that reframed IBM's approach to messaging our application modernization capabilities, drove a drastic improvements to the digital experience, and a 2x increase in product page to trial signup conversion.

In order to maximize our research footprint and drive alignment on the journey, Ashley and I convened a standing cross-organizational "Journey to Cloud" research group including senior stakeholders in IBM Hybrid Cloud, IBM Cloud, Data & AI, and IBM Garage.

User experience practitioners in Cloud actively contributed research to a shared client application modernization journey.

“Developers are way more opinionated about their approach. One [serverless] isn’t really better than the other. But developers need to know that we offer it.”

Developer Advocate, IBM

“You have to go through a huge web of bureaucracy to get a vendor. If a cloud service is missing something that's vital to a project, that's a make or break…We would have to have a really compelling reason to cut across clouds.”

Architect, Fairway

Stories

Our synthesis uncovered surprising insights that reframed IBM's approach to messaging our application modernization capabilities, and drove a drastic improvements to the digital experience and a 2x increase in product page to trial signup conversion.

As importantly, my storytelling aligned IBM teams on a shared understanding of how to improve one of IBM's most strategic customer journeys. The story we told was clarifying, not only to new designers learning about the hybrid cloud domain, but also to seasoned Garage professionals, who reported newfound clarity in their role. IBM Cloud, Data & AI adopted our journey model as the shared basis for their persona and journey library, serving every offering team in Cloud, Data & AI.

But, I think, as importantly, I found great joy in revealing this world to IBMers, many who had found themselves themselves alienated, bored, jaded or frustrated by their inability to understand or see relevance in the domain. The world of app modernization is full of drama. Stories of catastrophic hardware failures, political intrigue, organizational crises and near-death experiences abounded. Businesses cited the need for survivability, security, agility and yes, cost reduction, as key drivers of their move.

At Verizon, critical messaging infrastructure was being moved into scalable cloud environments after peak events like Mothers Day overloaded text messages and dropped heartfelt messages. At the Guardian, a series of heatwaves in London in 2015 that crippled both their primary and backup data centers also ground their publishing capability to a halt, prompting a rehosting effort into the cloud. At Hertz, a company on the verge of bankruptcy hadn’t released any new experiences to customers in 3 years, hampered by monolithic architecture and cryptic back-end services written in COBOL and FORTRAN.

Below: An excerpt from the highest-level of a story-driven framework I developed as a high-level synthesis of the application modernization journey. Deep dives into key steps were provided as well. To this day, this journey and its associated data remains the scaffold to our organization’s understanding of the modernization journey.

App modernization isn’t the language in the lab or online.

Although the phrase “app modernization” is commonly used by IBM and competitors, clients don’t actually use the phrase “app modernization” to describe their projects, nor do they search for it online.

In person, clients more often tend to describe their projects based on their specific issue, need, method or domain (e.g. “replace legacy CMDR with Salesforce”). Architects describe their work as “breaking apart the monolith.” Developers describe it as “writing a new microservice.”

Rather than focusing on "app modernization” as a whole, drive conversation around the methods or particular domains (microservices, kubernetes, containers) in which someone is modernizing application code, improving their infrastructure, architecture, and/or practices. This would improve IBM’s mindshare in the domain and expand it.

Individual technologies are commodities. Expertise wins.

Although the selection of a delivery partner is a big deal, decisions about specific technologies used for a given function on the project are not. Organizations will use a diverse range of tools to achieve their app modernization journey.

To business sponsors, there isn’t a ton of differentiation between, say, private clouds. (ICP or OpenShift? Kubernetes or Docker Swarm?). The director of IT at Hertz made clear to us that the decision to go with ICP was baked into the decision to go with IBM Cloud Garage, but, in his own words, “it doesn't matter to me.”

Furthermore, clients evaluate complete bundles of offerings together. Clients have a vested interest in minimizing the number of vendors and platforms that they rely upon for a project. Getting approval for a vendor within an organization is time-consuming and impedes one-off use of vendor offerings. If we improve the discoverability of related offerings in the catalog, we would drastically improve digital conversions, in batches of offerings at a time.

That said, past precedent dictates present options. If most of your company runs on AWS, you’re going to fight to stay on AWS. As the saying goes, “the best car is the one that already drives.”

IBM Cloud Garage is the most suitable lead-with solution for this journey. If we structure Garage offerings around key journeys, and align our offering strategy to fill gaps that arise along these key journeys, IBM would become the source of truth for modernization journeys in the market.

Modernizations are also cultural transformations.

“Application modernization is 20% a technology journey, and 80% a practice and policy transformation journey,” says Kyle Brown, IBM DE and architect. This means changing the way people work. It takes leaders and teachers to do the work.

Lift & shift migrations are easy, but they’re rarely cost-effective without refactoring monolithic applications. The real work is refactoring monoliths into independently operated microservices – which also means pushing devops culture through oftentimes resistant organizations.

One developer at MITRE Corporation, when interviewed about his technology stack, continued to pull the conversation in a cultural direction: “This kind of thinking will get you sidelined in an unfriendly organization” – he also reported that IBM Cloud Garage is the most compelling offering in the cloud adoption space he’s seen.

If we have cultural transformation discussions at scale, we would win legacy app modernization deals at a significantly higher rate than leading with the technology.