Human-centered design for the digital age

Summary

Defined and authored IBM’s POV on the application of design thinking in continuous-delivery digital enterprises, creating the world’s first design thinking framework with 3rd-party analyst-verified impact: average of 75% decrease in design & planning times, 2x increase in delivery velocity, and 300% ROI.

Developed a curriculum and rubric for the certification of key roles in an innovation ecosystem. Formalized IBM’s adoption strategy into a program that activated and certified over 400,000 IBMers and clients in Enterprise Design Thinking.

Collaborated with CIO, finance organizations and software vendors to design business processes enabling IBM teams to procure world-class virtual collaboration tools used daily by every IBMer, including GitHub, Slack, Mural, etc.

The case for design thinking at IBM

In the latter half of the 20th century, IBM's expertise in mainframes like Sabre and System/360 was unmatched by competitors. But as mainframes and network storage became increasingly easier to replicate and manufacture across the industry, competitors began to offer similar capabilities at a lower and lower cost.

In March 2014, a price war broke out among Amazon, Google, and Microsoft, as each announced cuts of as much as 35 percent on computing; 65 percent on storage; and 85 percent on other services. As basic IT capabilities have become ubiquitous, their strategic importance diminished – meaning for IBM, technology was no longer a reliable differentiator in the market. Meanwhile, companies like Apple, Netflix, and Facebook had been elevating consumers' expectations for what technology could do for them, and they were bringing those expectations to the places they worked. Faced with competition from firms that offered continuous innovation, pay-as-you-go fee structures, and freedom to exit any time, IBM could no longer rely on long-term contracts for unchanging systems.

IBM found itself catering to an entirely new group of customers that it didn't quite know how to understand: not CIOs and IT administrators, but doctors, salespeople, lawyers, teachers –– the people who actually used the solutions IBM offered. This new class of user didn't care to understand the intricacies of IT software. Their concerns were to become better doctors, salespeople, lawyers, teachers – and they didn’t want to open a bunch of .json files to do it.

All this left IBM with a existential predicament: a gap in empathy. We didn't understand our new customers, their wants, needs, and expectation. They certainly didn't understand us. So emerges the threat of competitors whose offerings cater directly to the needs and expectations of this new class of user.

In 2012, with the establishment of the new IBM Design program, IBM set off to close the empathy gap and regain its position in the market. At the heart of this mission to reshape the enterprise was IBM Design Thinking: a framework intended to help cross-functional teams collaborate to deliver better user experiences.

Borrowing heavily from the Stanford d.School’s design thinking competency, the first iteration of IBM Design Thinking relied heavily on the socially engineered opportunities afforded by face-to-face workshops.

Challenges arose early. Churn and rework rose across teams as they struggled to implement the process. New designers, citing a lack of understanding of the domain or customer need, regularly pumped the brakes on projects already in motion; even as engineering teams, invoking “agility,” continued to ship new code for features with questionable user value. It was not unheard of for teams to go for months without seeing return on their design thinking investment, leading key stakeholder to lose faith in the practice.

Of the original seven Hallmark project launched in 2013, three of them remained viable 12 months later. What IBM may have gained in its capacity for empathy, it seemed to have lost in its capacity for impact.

It was against this troubled backdrop that I was asked to serve as Program Lead for IBM Design Thinking. During my tenure, I uncovered philosophical and structural blockers to IBM’s successful application of Design Thinking. Having studied the success and failure patterns on teams practicing design thinking, I authored, published and drove adoption of a new framework canonizing IBM's point of view on human-centered design in a digital, continuous delivery environment. The framework became an iconic symbol of our design transformation and catalyzed a paradigm shift in the way the industry practiced design thinking, becoming the first design thinking framework with independently verified economic impact.

Later, I co-led research into the team makeups that produced successful projects. I leveraged those insights to design and deliver the Enterprise Design Thinking badge ecosystem and the Enterprise Design Thinking learning platform. Our work scale the number of activated IBM Design Thinkers from the 1,000’s to 100,000’s. The impact of this work on the culture of IBM endures today.

“If it doesn't work for a 5th grader, it doesn't work.”

In June of 2015, Adam Cutler and I travel to Dublin, Ireland to present a project to four IBM interns from the Institute of Art, Design & Technology in Dun Laoghaire. They have no software experience, have never worked in an enterprise setting, and have never heard the words “design thinking” before the project.

“Here’s the problem in a nutshell,” I attempt to explain. “People think Agile and DevOps are at odds with IBM Design Thinking. There’s too much confusion about how they don’t know how Hills map to Epics and User Stories. And we’ve just put in place a new product governance model called Offering Management.”

As this sentence rolls off my tongue, one of the interns goes pale. Another slumps back in their seat, eyes wide with what I interpret to be terror. Adam interrupts to tell me, in no uncertain terms, that they have no idea what I’m talking about.

That evening in my hotel room, I begin to panic. Like many others, I came into IBM as “the intrepid ethnographer,” studying the ways of The Corporate World from an arms distance. But there comes a time in every IBMer's career where they realize that they’ve assimilated. They’ve picked up the language. They’ve co-opted the rituals. In development labs and design studios, they have become peers; to the people they come home to every night, they have become space aliens.

At the end of our first week with them, the interns hold a Playback to us, where they present a persona: "This is Sarah, a 5th grader from Dublin. She likes bike rides, books, and blueberry muffins." Here, the interns bring us to the first requirement of IBM Design Thinking: “If IBM Design Thinking doesn’t work for Sarah, it just doesn’t work.”

From strict specification to continuous conversation

Prior to IBM, I was an industrial designer. My first job concerned the design of things like laparoscopic surgery instruments and dental drills. The world I once knew was the world of industrial manufacturing: a world of three-year release cycles and a "get it right the first time” attitude. As I entered the realm of software design, I quickly realized that the two design practices don’t even follow the same rules of physics.

Imagine for a moment that you work for a product design agency. A major consumer appliances brand has asked you to help bring a new washing machine to market. How would you do it?

You might start by taking time to uncover customers’ potential needs. You’d explore possible options. You'd likely prototype a few possible options, and evaluate the best ones, iterating until you reached a suitable answer to the problem. At some point, however, you have to draw up the specifications and send them over to a factory. A few days later, the factory might reply with a quote: $500,000 for the tooling upfront, $50 dollars per unit afterward.

A factory can say this with a lot of certainty, because in general, material properties and the production processes used to shape them are well-understood. Once you'd arrived at a design and you've passed the specifications over to the factory, your work as a consultant was largely over.

While design has always been about navigating ambiguity, the goal of industrial manufacturing has always been to eliminate ambiguity. It achieves this through a combination of well-defined specifications, robust tooling, and economies of scale.

It’s this world for which design thinking was originally canonized: a world of uncertainty in design, but certainty in implementation. It’s the world familiar to product design consultancies of yesteryear, many of whom helped push design thinking’s agenda through the 20th century.

There was a time when the world treated software development as an industrial manufacturing process too. Back then, a design team might do months of design work before passing specifications off to the development team. The development team would write the code, another team would do quality assurance, and yet another team would be responsible for getting it onto a CD.

Things are different today, of course. The latency between a design decision and a user outcome is approaching zero. A modern high-performing software team can deliver game-changing improvements to a product in a two-week sprint. We can A/B test and feature-flag. We can prototype in-market, double down on successes and roll back failures.

So while it’s important to move and act with intent, it’s just as important to release early and adapt to changing requirements. In an as-a-service world, our commitment to users no longer ends when they’ve “purchased the product.” As our users’ needs grow and evolve, they expect our offerings to grow and evolve too – should we fail to meet their needs, our users are free to cancel their subscriptions and end their relationship with us.

“We can't seem to get out of the ‘understand’ phase,” Temi once said; and in the most important way, she is right: in an environment changing as quickly as ours, the only way to understand is to engage.

“We can’t seem to get out of the ‘understand’ phase.”

It's August of 2015 and I'm on the phone with Temitope Ogunyoku, a researcher stationed in the IBM Research Nairobi Lab.

Temi's team has been challenged with finding a way to collect data about the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, and present that data to public health experts on the ground. Temi has been pushing her teams in the lab to take a design thinking approach to their research projects. But they’ve struggled to come to consensus on the right thing to build.

Meanwhile, the virus raged on across the continent.

"We're scientific researchers," she says, somewhat exasperated. "There's a fear amongst scientists in IBM Research of making a decision that might prove wrong later. We can't seem to get out of the Understand phase.”

If you didn't study to be a "creative," the uncertainty of coming face to face with a blank canvas can be paralyzing. What do I paint? Where does the first brushstroke land? What if I do something wrong? This cycle of doubt and inaction has a name: analysis paralysis.

Meanwhile, those of us who went to school for things like design, creative writing, art have spent spent years learning to solve the blank canvas problem. We've learned that it's only through abductive leaps of intuition that the desired future reveals itself, and that it's only through failure that we come to learn. In order to understand, it is often necessary to act.

So here we arrive at the second requirement: in the midst of uncertainty, IBM Design Thinking must be a model for action. If nothing more, it must compel us to try, fail, and learn.

Framework

The models that ultimately endure are the ones that are simplest to remember. Chosen for both its timeless, almost mystical quality, we intended the Loop to act as a sigil, a flag, a persistent reminder for anxious decision makers that everything is a prototype. Its powerful imagery and stark simplicity inspired a wealth of derivative material (and more than a few tattoos).

The new framework broke from the then-dominant linear, manufacturing-oriented approach to problem-solving, in favor of an iterative, service-minded approach to delivering great user outcomes. Today, a Google Image search for "design thinking” will return as many references to the Loop as to the linear Stanford d.School model.

/design/thinking

I defined the user experience, authored all content, and collaborated with Ryan Caruthers on the visual design of the digital property. Published externally to IBM.com, the Enterprise Design Thinking website articulates IBM’s unique perspective on human-centered design in simple language anyone – including the 5th grader – could pick up and understand.

The first iteration was modest; it contained a brief history of the program, an overview of the new framework, and a small toolkit of commonly used methods and activities.

The property eventually evolved to become the Enterprise Design Thinking digital learning platform.

To arrive at a new framework, Adam Cutler and I spent 6 months on a “listening tour” of teams that had successfully delivered good outcomes, then went back to our desks and illustrated their stories back to ourselves. We covered every inch of the IBM Studio in Austin with a line, a swirl, a diagram. We took notice of our own behavior too, slowed our own design processes down to a crawl, and recorded what we were doing: observing, reflecting, making, and repeating.

I knew we’d stumbled upon something special as soon as I started using these stories to teach new designers. In an A/B test with six bootcamp teams (three control), teams that received instruction on the new IBM Design Thinking framework reduced the time to deliver tangible prototypes from three weeks to two days and were estimated to have doubled their output of ideas.

Top: The Principles describe the values that underpin IBM Design Thinking. They also serve as a lightweight object model, a continuous conversation between users, their needs, and the teams solving for them.

Middle: The Loop is a behavioral model that describes the iterative nature of conversation: observing, reflecting and making to continuously drive improvement and understanding.

Bottom: The Keys describe specific tactics that enable our teams to participate in conversations to happen at the speed and scale of modern digital product development.

Loops

Understanding IBM Design Thinking in 10 minutes

Viewed over 300,000 times with over 100 comments, the “Understanding IBM Design Thinking in 10 Minutes" unpacks the IBM Design Thinking framework in an accessible way for all audiences.

Adoption

A practice cannot be considered complete until it is applied and adopted.

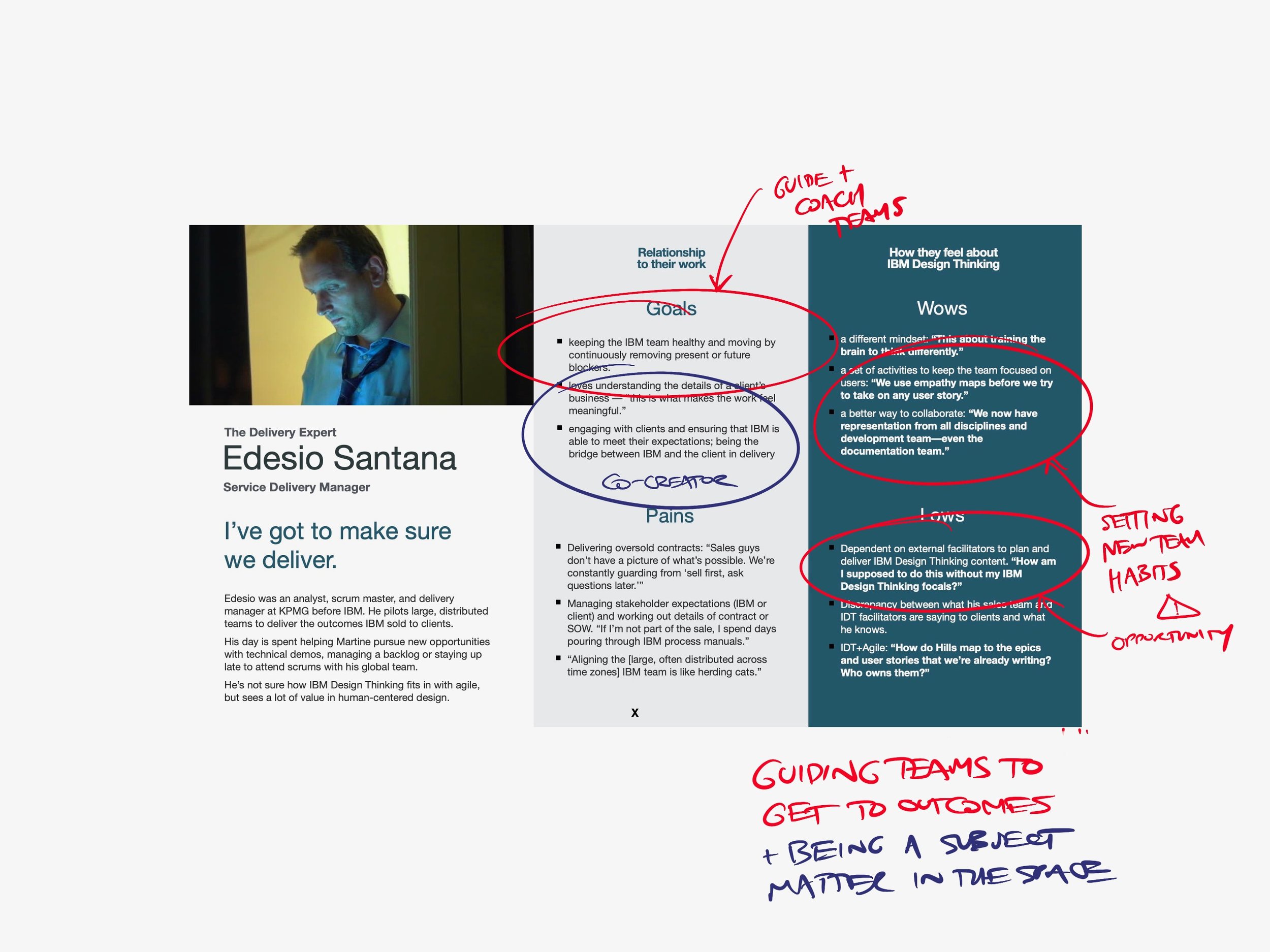

To identify opportunities to drive broad adoption of the practice, I worked with Jordan Shade to co-lead new research, embedding with product teams and client-facing consulting teams to uncover the patterns that produce successful projects. Outside of IBM, I found a community of like-minded researchers in the Design Thinking Exchange – a community of academic researchers and transformation leaders in large enterprises and public sector institutions who validated many of the patterns we were uncovering.

The insights from our research revealed a topology we could exploit to successfully change behavior and drive adoption of human-centered design across an organization resistant to change.

Certification

The insights from our research ultimately led to the definition of a practice ecosystem consisting of 4 distinct practices. The ecosystem described how team members of different roles contribute to a healthy microclimate. I developed the expected skill set and rubrics for mastery of each role, which became the basis for Enterprise Design Thinking's formal certification program ("Badges").

Organizations both within and beyond IBM adopted these certifications as indicators of proficiency and trust, and as an aid to staffing healthy project teams. IBM Services teams used these badges to appropriately staff critical client engagements with trusted, credible design thinking leaders, while IBM Software deployed squads with at least 1 Coach. In our technical sales organization, IBM Garage mandated every member of their organization to achieve a Co-creator certification, and issued a target staff of 1 certified Coach to every 16 Co-creators.

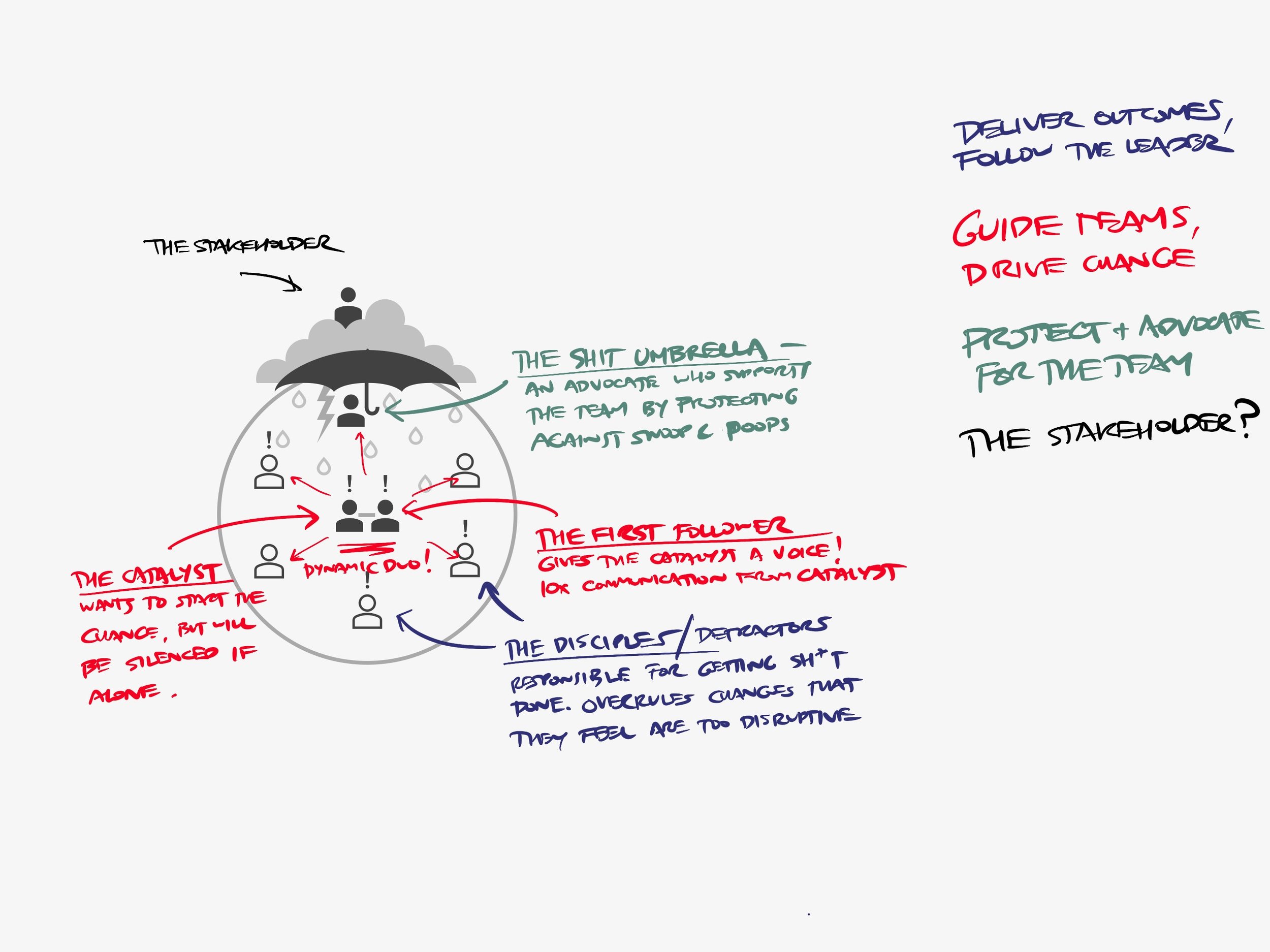

The Shit Umbrella

Another particularly ubiquitous pattern: a catalyst joins a team set in its ways. Alone, the catalyst is generally sidelined by the team’s inertia; but when the catalyst is joined by just one (occasionally planted) first follower, they are provided the platform to vocalize and verbalize their perspective. (If you’ve ever had a “work spouse,” you are likely familiar with this pattern).

They form a community of two, eventually drawing in the rest of the team. This microclimate holds, so long as there is no outside interference on the team. The catalyst and follower need at least one strong advocate to protect from outside interference, like an “Executive Swoop & Poop.” For this reason, we lovingly called this microclimate the “Shit Umbrella.”

Not all design thinkers

A key takeaway from ecosystem research: not every design thinker has the same responsibility in the ecosystem. Indeed, some are responsible for things like research, synthesis, protoyping and delivery. Others play a capacity-building role, guiding, mentoring, and up-skilling teams to become better design thinkers. Still others design thinkers are accountable to the success of a their business, by whatever means.

An error often made at this point is to train these stakeholders on the same practices used by a delivery team (e.g. send them to an “executive design thinking workshop”). Indeed, most human-centered design education does not differentiate their practice education to serve these roles. However, we’ve found that being a good stakeholder is a distinct practice with distinct objectives and methods.

Scale

In 2017, IBM Design Thinking was renamed Enterprise Design Thinking, reflecting the broad applicability of the practice not only to IBM, but any large enterprise. Based on the success and interest in our newly minted certification program, the General Manager of IBM Design issued our team a new target: 200,000 badged Enterprise Design Thinkers by the end of the year.

This was not a number we were prepared to meet. It was also not one that our roving teams of enablement and education specialists had any hope of achieving. At the current rate of in-person activations, it would take them 40 years to reach that number.

Although initially skeptical of digital learning experiences, my team and I managed to design a curricular learning experience and accompanying in-person and digital touchpoints that scaled our reach and ultimately exceeded our target by the end of the year.

Chapter Network

IBM Design Thinking University Chapters are communities of practice led by an IBM Design Thinking Leader who mentors the group. A person joins a Chapter with the explicit goal to grow her IDT mastery in order to achieve transformative user-centered outcomes on her teams as well as next-level badge status.

The Chapter Model is both the way we scale our ability to evaluate IBM Design Thinkers and award badges, as well as the way to connect disparate practitioners with communities of other passionate adopters around the world.

Digital Learning

To accelerate adoption of IBM Design Thinking and minimize the burden and operating costs associated with in-person trainings, I designed, produced, and delivered "one of the most immersive virtual/e-learning assessment experiences at IBM.”

The first iteration revolved around a hands-on case-based learning and assessment experience, educating IBMers on concepts from design research and synthesis to prototyping and user-centered governance. In just 6 months, IBM Design Thinking University had awarded over 40,000 Practitioner badges.

Demand for expanded learning content grew. Having proven product-market fit, I developed the prototype for the V2 iteration now known as the Enterprise Design Thinking learning platform. The platform went on to certify 330,000 IBMers, clients and partners in Enterprise Design Thinking.

Quantified impact

With the release of the Forrester Total Economic Impact study, IBM Design Thinking became the first design thinking framework whose economic value was independently verified by a 3rd party analyst, bolstering IBM's eminence and respect in the human- centered design community. Teams applying IBM's Design Thinking practice saw a 75% decrease in design and planning time; 2x increase in team velocity; 300% ROI.

“We were always taught in school

to save making for last. The Loop

gave us the permission to make,

and fail, and try again in a way

I’ve finally internalized.”