The hundred-year system

Summary

Summary

Background

IBM is in an exclusive club of centenarian companies – companies that have managed to endure for over 100 years and still retain continuity in their identity, management and governance systems.

That makes us an outlier at a time when the average lifespan U.S. S&P 500 company has fallen by 80% in the last 80 years (from 67 to 15 years). A recent statistic from the Bureau of Labor revealed that that only 36% of companies last 10 years. About 21% make it to 20. The 100-year company is so rare that it's hard to calculate how rare they are, but the current estimate is about half a percent (0.5%).

The survival of any enterprise is largely dependent on how well they adapt to change, but also how efficiently they can execute their goals. Building a system of governance that can endure for 100 years is a tall order in and of itself.

Design. System.

Before I go further, I want to explain our use of this term at IBM.

These are two of the most substantive words in the English language, and yet when we concatenate them, we tend to arrive at something that resembles a "component library full of buttons and other things."

I'd like to offer a more generalizable definition:

By Design, we mean the decisions we make toward an intended outcome. Most of us in this room would agree that design concerns decisions about every aspect of an enterprise, from who we are, to how we behave, to what we offer and how it manifests.

By System, we mean governance. This concerns who makes decisions, how these decisions get made, how they get consumed and scaled, how they get passed on. We build these governance structures in order to scale ways of learning, processing and deciding.

When we use the term "design system," we don't just refer to our elements and component libraries. We refer to the decision-making infrastructure for the organization as a whole.

The Philosopher King and the Dark Ages

In the early 1950s, Thomas J. Watson Jr. is walking down 5th avenue in New York, when he is drawn in by the allure of an Olivetti shop. The products have sleek designs and are bright and colorful. Inside, the shop is clean, bright and modern. But importantly, Watson Jr. is taken aback by the contrast with his father's company: dimly lit offices and displays full of drab and boxy, dull and lifeless products.

The experience with his father's competitor leaves a profound impression on him. When Watson Jr. takes over his father's role as IBM’s chief executive, he resolves to leave his mark on IBM through design.

He hires Eliot Noyes, an industrial designer he knew from his time at the Pentagon. Noyes’s goal was to create a first-of-a-kind corporate design program that would encompass everything from IBM’s products, to its buildings, logos and marketing materials.

Noyes had the radical idea that everything didn’t need to look alike, and he brought a kind of creative philosophy to his work he called "architectural thinking," which enabled teams to do complex projects without micromanagement – a sort of early example of the doctrine of commander's intent. The goal was not consistency, or uniformity, but unity. To bring that vision to life, Noyes brought in a wide variety of some of the greatest creative talents of the day: artists, designers and architects like Charles and Ray Eames, Paul Rand, Eero Saarinen, and Isamu Noguchi.

Noyes' design program heralded the heyday of modern corporate design. IBM was the company to beat– the first modern "design-led enterprise." Every modern corporate brand today owes their success to IBM's design legacy.

So the question is: where did it all go?

Answer: it went with Noyes.

After Noyes’ death in 1977, the IBM design program and the assemblage of modernist design heavyweights, along with their ethos and work ethic, began to wither away. Noyes had built a world-class design program that changed IBM forever, but it relied heavily on a few experts and leaders from outside the company to sustain it. When those leaders disappeared, no system existed to replace them.

In the absence of the design leadership, brand expression and experience that Noyes had build, product development becomes an engineering-led effort to drive consistency and efficiency to product development. If Noyes was IBM's philosopher king of design, his death heralded the beginning of a long dark age.

The Renaissance and the City-State

When IBM Design is revived in 2012, we knew we had to do it differently. Reflecting on the mistakes of the past, our head of design, Phil Gilbert, issued the program a mission "…to establish a sustainable culture of human-centered design and design thinking" – one that would outlive the individual designer, and that would embed design into the fabric of the enterprise.

Over the next 7 years, IBM goes from a handful of contractors and agency partners, to a workforce of thousands of full-time, formally-trained designers. Design is given first-class status as a technical discipline, on par with engineers and business leaders, with formal career ladder and path to advancement in the enterprise. In just a few years in, there are design executives embedded in every business unit at IBM, across corporate functions, software product teams and consulting services, spread across the world.

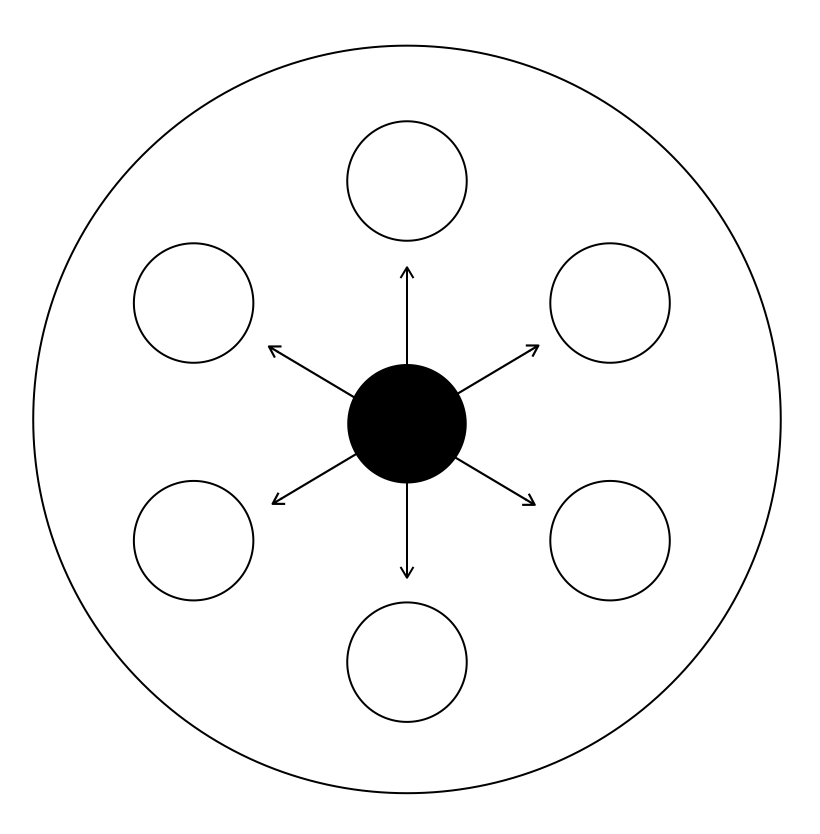

These designers are based in a network of over 96 global studios. In the spirit of embedding, these studios were integrated into the existing campuses and facilities that IBMers already worked. (The rationale was simple: "If the business doesn't see design in their teams, providing value everyday, then some executive will see design on the expense sheet and it will become the first victim during a bad quarter.")

Power in this system is decidedly decentralized. Teams are given high-level directional guidance, and the remit to operate as needed within their context. The first IBM Design Language is released. It is a design language, not a component library, aimed at breaking decades of componentized, authoritarian patterns introduced in earlier years. When IBM Design Thinking is published, it is a framework, not a toolkit. It's aimed at breaking us away from the ordered, stifling weight of process gates and checklists that passed for product development in a previous era. Such a permissive environment helped IBM Design become a hotbed of design and innovation.

Having rebuilt our capacity to apply design in our products and services, and embedded design and design thinking into the fabric of the company, IBM had achieved its goal of building a sustainable culture of design. No individual at IBM would be powerful enough to take design away. The renaissance was in full swing.

But the result of this decentralization is very curious. At the individual product level, we see incredible success. Usability scores are up. CSAT scores are up. Net Promoter Scores rise by 50 points in some portfolios.

Yet an increase in the quality of our products did not translate to better experiences for our clients. For one, our customers rarely rely on just one IBM offering – they compose them together it higher order solutions. With little shared foundation, teams hardened their own operational infrastructure, building their own management practices. By 2017, IBM found itself maintaining 16 distinct design systems. Customers experienced up to 12 various login patterns. Every product using a natural language processing relied on a different, bespoke technology stack.

In the words of one major client: “I can’t tell if you’re one company, or one hundred of them.” Without unity and interoperability, there was no correct total statement. If we chose to continue this way, we would fail to live up to the idea of corporation as a good painting.

Empire

What was once a tight knit circle of trust had become highly distributed, loosely connected, lacking shared identity.

In 2017, the IBM Brand team set out on a complete overhaul of IBM’s design language, to be based on the duality of Man and Machine, and a sweeping reduction in inconsistency and idiosyncrasy across products.

Consider typography. All IBM products would use a single type family – IBM Plex – and type scale.

Or, consider the use of color. Once known as Big Blue, IBM now leaned into blue as the primary color in all digital experiences.

Pulling it all together was a comprehensive spatial framework built on divisions of 2 — a universal grid that applies to all formats. With this ‘2x grid’ we’re aiming to bring the same rigor of traditional grid systems into other media, especially digital.

In order to execute our brand in our software and to deliver on the works together, works the same, works for me portfolio strategy, we needed not only a design language but a design system.

Translating that vision to a single design system of record for IBM that would unify a software portfolio of over 3000 products was the Carbon Design System. Carbon is an open source system consisting of working code, design tools and resources, human interface guidelines, and a vibrant community of contributors.

The Carbon Design System began its life in the Cloud organization (in 2016) as one of 16 design systems at IBM. Three years later, all 32 production-ready components had been restyled and retooled to execute the brand team’s vision, and v10 of the Carbon Design System was launched.

We had a clear, overarching design ethos and principles to guide us in all manner of decisions. We had a corporate strategy that would bring cohesion to our sprawling portfolio. Having a comprehensive language and supporting system in place meant that no matter how a person interfaced with IBM, whether they were at an event, in a product, or even talking to an IBM employee, there were a set of values in place to move people thoughtfully forward, end-to-end. The pendulum of our system had swung back to centralization, unity, shared values.

We’ve certainly ended this story here before with a pat on the back. But as they say: History doesn't repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme.

The centralization of core decisions led to tension between the "core" system and its consumers and contributors. A single, rigid global system, governed by a single authority unable to account for the complex use cases and contexts simply couldn’t address the needs of 300+ products. Almost immediately following the launch of Carbon v10, local systems we called “Pattern Asset Libraries,” or PALs, began to emerge to serve the different business units: Cloud, AI Apps, Cloud Data and AI, Security, Watson Health, to name the largest big ones. Between them, bad blood prevailed.

The Republic

So what has our experience with design governance at IBM taught us about how to govern for the next 100 years?

IBM’s first iteration relied on the titans of modernism. We owe it to them for the invention of modern corporate brand. But it also disappeared when those titans disappeared.

Our second iteration pushed people, decisions, knowledge out into the peripheries. It led to flourishing city-states. But it also led to the failure to bridge the distances between silos.

And our third iteration consolidated decisions toward centralization. It led to unity, but it also sparked discontent and risked uniformity.

We've been asking ourselves: how do we build a more perfect union? A learning system that grows and changes and adapts to the needs of its constituents? A system held together by shared beliefs but that learns from its peripheries?

In order to fulfill IBM's hybrid cloud ecosystem strategy, IBM teams must not only deliver excellent experiences for themselves. They must also support the integrity of the ecosystem by delivering offerings that work together, work the same and work for customers.

Forests over trees. Wholes over parts. This is not habit at IBM. Significant social and technical blockers still stand in our way.

We have a strong culture of invention, but this also means we tend to reinvent the wheel. How do we cultivate open- and inner-source communities that reuse and contribute to shared resources, so we can focus our energy where it’s needed most?

We know how to build great standalone products, but struggle to design with the broader ecosystem in mind. How do we incentivize teams to transcend silos and prioritize our common interest as One IBM?

"In a sense, a corporation should be like a good painting; everything visible should contribute to the correct total statement; nothing visible should detract.”

Eliot Noyes

In 2019, IBM acquired Red Hat, and with that acquisition came one of the most significant shifts in our portfolio strategy. We were to become a platform ecosystem: a portfolio of software products, infrastructure offerings, and consulting services atop a common hybrid cloud platform.

Ecosystems thrive on an exchange of value between customers and providers, we studied the principles of what makes healthy platform ecosystems, and divined 3 simple principles for teams to uphold.

Platforms must ensure that customers have an excellent experience with the ecosystem:

Works together

Product interoperability

Our products have to be interoperable so that customers can compose complex solutions. Customers must be able to make the products on the platform amount to more than the sum of their individual parts. This requires common concepts to be adopted across offerings in the ecosystem.

Platforms must make it easier for providers to meet standards than to diverge or duplicate.

Good

Teams need to be able to deliver an excellent experience that reflects positively on their reputation.

We don’t deliver a coherent experience to our teams to create experiences that work together, work the same, and work for me.

Works the same

Experience consistency

Complex workflows take users across multiple products. Customers consuming a product on the platform should have a consistent experience with other offerings in the ecosystem. This requires common interaction patterns to be adopted across offerings in the ecosystem.

Fast

Teams need to deliver new capabilities quickly, on a continuous basis.

Works for me

Fitness for purpose

Our users’ trust is earned one excellent experience at a time. Nobody buys into a platform full of 1-star products, so every product has to deliver a useful, useable, desirable experience, in its own right.

Customers must have a great experience fulfilling their specific needs as individuals. This requires a common bar for performance against user needs and expectations.

Cheap

Teams need to deliver new capabilities with minimal investment of resources.

The 100-year system is not a component library

At IBM, we've spent the last year and a half studying dozens of teams, asking them to show us all of the ways they onboard new team members.

Combing through all of these resources, we found that we were able to categorize everything they offered teams into just one of 4 supertypes.

First: things you can measure an outcome against. Business goals, customer requirements and definitions of "excellence," or "standards" for interoperability or consistency. Ethical standards, accessibility, platform requirements, ethics, HIPAA, SOC2. But also product-specific goals, like design principles, user stories, etc. Let's call them "standards."

Second: things to be integrated directly into a product experience. Reusable components, patterns, code libraries, content blurbs, but also reusable tech like an open- or inner-source NLP stack. Let's call them "assets."

Third: behaviors, processes, methods, and other ways of acting. A business unit operating model. Service design methods to co-create with clients. Pre-release stage gates. Let's call them "practices."

Fourth: knowledge that we've gathered about our users and customers, domains and markets. Personas about data scientists, canonical customer journeys, common customer app modernization use cases. Let's call them "insights."

Object schemas

A clear schema around each of these object types enables us to process and index any kind of content. A very complex piece of reusable thought leadership can be decomposed and absorbed into the pieces that can be reused by teams.

Even within the Asset category — which we were closest to — we found that we hadn't yet agreed on shared definitions of all the asset types across the ecosystem: Components, Functions, Patterns and Templates.

Once we agreed on asset types, our team worked with our product partners to develop a schema around each of these assets that enabled us to categorize and index all of the content coming out of the teams.

For example: Assets have a type, a status, they're written in a framework, etc.

We found that the schema model worked well for the other object types, like Practices and Standards as well.

The 100-year system delivers an excellent provider experience

The 100-year system must make it easier to do the right thing than to do the wrong thing. And it must give to its users as much as it asks of its users.

To the dismay of heavy-handed enterprise leaders, participation is often a choice. When it is difficult, slow, or disadvantageous to participate in a system, your teams will choose to strike out on their own, duplicate, diverge...which leads to disunity.

So the first step to delivering coherent experiences to our customer is to deliver a coherent experience to ourselves.

Improving how teams discover and build

At IBM, we studied how teams drew from system resources in order to design all sorts of experiences. And not surprisingly interesting about those object we discussed earlier is that they’re almost never used in isolation.

Let’s say I’m building a product marketing page for my product. I’m going to need the product page template, but there’s also a 95% chance that I’m going to have to reference some sort of content quality standard...maybe reference the data scientist persona we're designing that experience for. I’m gonna need to learn to optimize SEO performance. So on and so on.

So we need to be able to index all of this content and build relationships between it.

We are working towards this mechanism with the new Carbon Platform… A single place to access and cross-reference all of these object types......and discover and consume all the (related) resources they need to deliver a great experience.

Did we have an early mock showing related resources somewhere? Might be more illustrative of this point...

Consider some of the best experiences that onboard 3rd party providers into an ecosystem.

Apple's provides a comprehensive Apple Developer experience, combining their Human Interface Guidelines with their platform guidance for Mac, iOS.

Airbnb rightfully gets a lot of credit for paying as much attention to its host experience as its guest experience.

If you want to drive for Lyft, you verify your identity, get a background check, tell them what car you have, and your product's ready to go on the platform.

Why shouldn't enterprises think about their own teams' experiences with the same degree of care? We think that's what the experience of participating in a system is really about.

The 100-year system is a learning system

Our history has also taught us about the careful balance between autonomy and authority. It cannot be unmanaged – that's how you get disunity.

But it also cannot be oppressive. The decisions made by just a few creative leaders cannot hamstring teams from their ability to do what is right for their context.

So how do we strike that balance?

M

Consider highway design in the US.

Some requirementsand standards truly are non-negotiable:

We drive on the right.

Green means go, red means stop.

Highway navigation signs are green rectangles and must use Clearview

M

But individual states and municipalities have specific requirements to conform to local laws, and publish supplemental manuals.

Occasionally, state norms are adopted universally. We no longer refer to it as a "California Right Turn," we just turn right on red.

M

At IBM, we need to design for a similar federal - state - municipal relationship.

Because some decisions truly are non-negotiable for teams to adopt to participate in our system.

- Everyone supports our corporate strategy

- Triple-A accessibility compliance

- Everyone uses the same Plex typeface

This is the common ground that unifies us as an enterprise.

As we go into different parts of IBM, teams make decisions and create resources to solve problems and drive efficiencies local to that space.

- IBM Cloud Platform has specific designs for catalog cards, details pages, components connected to platform services

- A small but important portion of our products have to comply with HIPAA standards

- Teams across IBM Sustainability rely on common insights about

There are resources specific to individual product teams too:v components that were invented for a specific product, specific insights about specific user tasks, etc.

Knowledge created locally is often of benefit to the whole system.

But too often that knowledge is locked away in silos, inaccessible and hard for others to learn from. So we intentionally had to create a mechanism that enabled the Local to inherit the Global; the Global to learn from the Local.

J

Example: Carbon Accountability Teams

For teams contibuting resources

Because no central authority could ever know all of the domain and problem that teams will face, we distribute governance to teams.

If a team in, say, IBM Security contributes a resource, it's difficult for someone without deep expertise in the cybersecurity domain to qualify that resource.

This federated logic is how we govern contributions and decisions in different jurisdictions.

J

Example: Standardized contribution framework

For Teams Contributing resources

Although we have a federated governance model, we need a standardized contribution framework across the organization. This is something we’ve also been partnering with product teams to develop over the past year.

J

Example (catalog filtration)

For teams consuming resources: in the near-term indexing our decisions by jurisdiction enables teams to filter down to the assets, practices and insights that are applicable to them.

J

Example (teams view)

So imagine: you join a team at IBM, you’re very quickly able to figure out: what customer requirements are we trying to meet? What customer use cases are we implicated in which components and patterns are applicable to my specific product? ...all without compromising the ability to learn from any team, anywhere at IBM.

This makes it easy for teams to identify resources that are compliant with their platform and domain, resources that would be convenient for their team to implement...or resources that might not be easy to use, but that, if implement, would help drive consistency.

A PDF field guide for new IBM designers to learn about everything IBM Design offers for them to productively contribute to their team's outcomes:

re-imagines the onboarding experience through the lens of our object model, dissolving the silos between our internal brand identities

tests our future-state information architecture and hone our system storytelling

uncovers gaps in our system blueprint

A designer, new to IBM, can find everything the IBM Design community offers for them to productively contribute to their team's outcomes.

A digital design system that streamlines the experience of using components and patterns from across the IBM community to meet standards of excellence will:

unify the discovery, consumption and contribution experience across business units

leverage the existing relationship teams have built with the Carbon Design System and establishes a pattern of collaboration with design operations teams across the enterprise

lay a foundation for an extensible digital property that accepts other reusable resources (e.g. practices, insights, teams, etc.

A member of a product team can discover and learn about resources [standards and assets] in the system with confidence in their completeness, who maintains them and where they're used.

Meanwhile, an IBM Maker should be able to create, document, and share new resources [standards and assets] to the system without DPO involvement or coding a documentation website.